|

If a tree falls

in the woods but no

one hears it, does it really fall? Who cares, trees come a dime a dozen

in the woods. But if that tree is stripped, chopped, processed, fashioned

into a guitar and placed into John Fahey’s plump and knobby fingers, will

anyone hear the sounds he conjures from it? Does it even exist? Yes and

no, in no particular order.

For the better part of four decades, John Fahey has existed in a vacuum,

cultivating contradiction, spinning innovation. His contributions to American

music are no less singular than those of some of the century’s true giants

— Bill Monroe and Louis Armstrong come to mind — and his influence is

only slightly less pervasive. Monroe and Armstrong are dead, and Fahey

has had a right mind (and body) to join them on a few occasions, but he

lives, modestly, in a motel room in Salem, Oregon, has for 15-odd years.

John Fahey knows his place is in this world, because there’s no suffering

in heaven. And without suffering, where would that leave him?

I HAD HEARD SUCH SOUNDS BEFORE...

To borrow again from Stanley

Booth (maybe he should be writing this piece), like every true original,

John Fahey has a strong sense of tradition. The components of his muse

— his steel string guitar, his country blues, his love of classical melodicism

and dissonance, his fascination with railroads and other manifestations

of the industrial age — all have their origins in the early 20th century.

Fahey is a formidable expert on the age. Growing up in Takoma Park, Maryland,

he fell in with some of the most rabid record collectors in the region.

Compelled by a love of early country and blues 78s, this charter group

of vinyl junkies embarked on frequent trips to the South, canvassing black

neighborhoods in search of records and the artists who recorded them.

Though cryptically recorded and packaged, Fahey’s own first album, Blind

Joe Death (ca. 1959, pressed in a quantity of 100 and sold, primarily,

out of the gas station where he worked at the time), reveals his love

of these musics and demonstrates his already keen grasp of their lexicon.

Not bad for a man barely 20.

By the early ’60s, Fahey had switched coasts and was enrolled in a newly

inaugurated graduate program in folklore studies at UCLA. The program

led to him visiting the South again with some frequency. On two such expeditions,

Fahey “rediscovered” blues greats Bukka White and Skip James, both of

whom would enjoy fruitful second careers (and in the case of James, an

arguable artistic peak; reference Skip James Today ca. 1966 and Devil

Got My Woman ca. 1968) during the blues revival of the day.

...A SIMPLE HUMAN EXHALATION...

Back in Los Angeles, Fahey

continued to cultivate his own playing. With the help of ED Denson, another

transplanted beltway native who oversaw the business end of Fahey’s Takoma

record label, he issued a series of recordings that defined his art and

earned his audience. Exhaustively titled albums such as Death Chants,

Breakdowns and Military Waltzes, Dance of Death and Other Plantation Favorites,

and The Great San Bernardino Birthday Party and Other Excursions bore

the heavy yoke of history, the isolation of timelessness, the exquisite

pain of a simple human exhalation. For some reason, the hippies loved

it.

Still, Fahey emerged from these lonely spiritual excursions with his humanity

and good humor intact. Like, say the Let it Bleed-era Rolling Stones (a

comparison he would probably loathe), Fahey suffused tradition with his

own talents so seamlessly that his innovations were often indistinguishable

from homage, or even hoax.

Reference Fahey’s 1968 album,

The Voice of the Turtle, an album of ragas, “field recordings” and sundry

guitar wizardry all bound by some impossibly dense and completely fabricated

liner notes (the first sentence alone is 561 words long), penned by Fahey.

Aping the academic, Folkways-style liner notes of the day, Fahey purports

that sections of Turtle date back as far as the ’20s. And if you weren’t

aware of his gift for gag, you probably would have believed him.

...LOSING IT, WAITING FOR

IT AGAIN...

By the ’70s, Fahey’s work

and interests began to splinter. Takoma recruited a many-striped stable

of Fahey protégés, from strict disciples like Robbie Basho

and Peter Lang, to new acoustic/age-stars-in-waiting Leo Kottke and George

Winston, to authentic weirdo Joe Byrd. Byrd’s psychedelic masterpiece

with his band the United States of America prepared no one for his subsequent

Takoma release A Christmas Yet to Come, an album of traditional holiday

carols as rendered by primitive synthesizers. The Takoma roster of the

’70s reflected Fahey’s belief that popular music reached its eclectic

peak, “its zeitgeist,” during that decade. Fahey himself supplemented

his Takoma output with inspired, if not definitive, recordings on the

larger Vanguard and Reprise labels.

As the ’70s stretched into the ’80s, the story became cloudier. Fahey

generated less music, likely because of a succession of personal and health

problems. A couple soured marriages, alcoholism, and bouts with Epstein-Barr

syndrome all sapped Fahey of some of his creative impulses. By the late

’80s, he had vanished from the musical vanguard as quietly as he had entered

it 30 years prior.

Hindsight reveals that Fahey spent his lost weekend in and out of charity

missions and dive motels, earning a piecemeal income as a different kind

of picker, finding collectible records in thrift stores and reselling

them for meager profits. In some ways, his life had come to resemble those

of his blues heroes he happened upon back in his UCLA days. It’s only

fitting, then, that he too would be rediscovered — by noted critic, collector

and Fahey fanatic Byron Coley — and with no small amount of encouragement,

would embark on the most prodigious phase of his career. With legend intact,

Blind Joe Death lived again!

...THE SOUNDS I COULD NOT

IDENTIFY, THE REALLY FRIGHTENING ONES...

1997. John Fahey, the notorious

cynic, the hardened bastard, talks with the wide-eyed mettle of a man

recently emerged from an extended tenure in a musical deprivation tank.

“I think this is a really exciting time for music,” he insists, “experimental

music particularly. People are a lot more open and curious than they ever

have been before.” And the new-fangled John Fahey is here to give the

people what they want. By the end of this year, Fahey will have added

five more albums to his already sizable canon, as well as a loosely autobiographical

book to be published by Drag City Press. He’s also re-entered the biz

by way of Revenant, his new record label, aimed at releasing “raw music”

from the likes of Cecil Taylor, Derek Bailey, Jim O’Rourke, Hasil Adkins

and the Stanley Brothers, to name just this year’s crop. The onslaught

begins with City of Refuge on Tim/Kerr Records, Fahey’s first release

in over five years, an album so good that in one fell swoop it erases

many of the transgressions of former colleague Winston and the host of

other players who claim Fahey as a formative influence. “I don’t understand

that connection [between my music and new age music] when people make

it, and I claim no responsibility for it.” Fahey says flatly, impatiently.

Sure enough, Refuge carries none of the traces of lobotomized minimalism

inherent to new age music. It’s Fahey’s most challenging — and, by his

own claim, his best — work to date. The album is more akin to the works

of a newer crop of Fahey descendants, groups like Gastr Del Sol and Cul

De Sac (both of whom Fahey has collaborated with in recent months).

Refuge opens with “Fanfare”, a nihilistic sound collage drawing on a series

of disparate sources from a train to a Stereolab song (the track “Pause”,

from Stereolab’s 1993 album Transient Random Noise Bursts with Announcements,

is “the only one of their songs I like,” Fahey says). On the album’s subsequent

five tracks, Fahey blends primitive acoustics with the occasional found

sound in thoroughly updated fashion. It’s as though he never left.

He saves his starkest work for the final track, “On the Death and Disembowelment

of the New Age”. Asked whether the song addresses the new age musical

genre or the new age of cyber culture, Fahey replies, “Both.” Of course.

Either way, I wouldn’t want to be on the receiving end of the song’s dark

manifesto, its unidentifiable, frightening sounds.

THE TRUE ADVENTURES OF JOHN

FAHEY

In his book of the same name,

James Rooney explains the concept of Bossmen:

“Every field has its ’bossman’ — the one who sets the style, makes the

rules, and defines the field in his own terms. Each man is aware of who

he is and exactly what he has done. Each man has thought deeply about

music and respects his music. Music has been for each a way of getting

at what is true and real in life.”

Fahey is a bossman unto himself. He invented a genre that only he seems

to understand, but he’s eager to share his talents nonetheless. His first-generation

students proved to be a mutinous bunch of turncoats, perpetrating lies

atop the truths and realities he showed them. But maybe Fahey is right.

Maybe now is the time when he will finally be understood, even cherished.

God knows it’s been a long haul to get here.

THE END

|

Matt

Hanks writes and talks about music in

Memphis, TN, where his employer swears he is

the very best babysitter.

|

Copyright 1997 by No Depression/Matt

Hanks. Reprinted here with permission. This article first appeared in

the May-June 1997 issue of No Depression

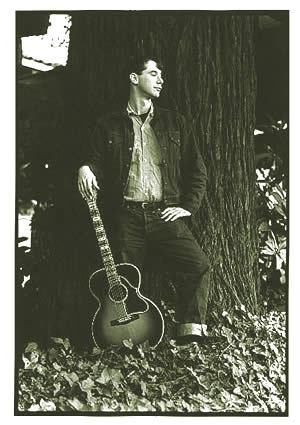

magazine. We thank them for allowing us to use the photo kindly provided

by the art staff at Fantasy Records in Berkeley, CA.

back

to johnfahey home

|