Reprinted here with the permission of

THE OREGONIAN, PORTLAND, OR

SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 1997

Fahey bedevils his listeners

again

By

JOHN FOYSTON

of

The Oregonian staff

A recent article in The New York Times about guitarist John Fahey cautioned

that influential American artists are often cranks recalcitrant and inscrutable.

Fahey is all of that and a wizard guitarist to boot but not

every one of the 300 or so people at the Aladdin Theater Thursday night

would agree with both halves of the Times assertion. Especially those who

walked out early, mystified by Fahey's spiky explorations of dissonance

and the internal harmonies of noise.

They were a small percentage of the crowd; most sat quietly for an

hour and several tunes until at the end of "Fanfare" from his new CD

"City of Refuge" Fahey glanced out at the room and said "Well folks,

that's about it for the show tonight." People clapped vigorously as Fahey

walked off stage without further comment. Though the lights stayed down,

the shouts of "more" quickly died with the applause clearly, he's

not an encore kind of guy.

Precisely what kind of guy he is has always bedeviled listeners. Brilliant

and eclectic come easily, but the rest of the description is elusive.

In the early '60s, Fahey seemed to be an acoustic revivalist and maybe

even part of the Great Folk Scare.

Fahey quickly shrugged free of any labels. "While other folkies

earnestly sang the "Wabash Cannonball" Fahey released albums such as "Death

Chants, Breakdowns and Military Waltzes" and recorded songs that included

taped segments of traffic over a bridge.

Chronic fatigue syndrome and drinking found him living in a men's shelter

in Salem in the 1980s. But Fahey's music never went away, and a surprising

array of musicians claim him as an influence, such as Leo Kottke and Sonic

Youth's Thurston Moore. Fahey regained his health and quit drinking and

has begun work on a variety of new projects. "City of Refuge" (in stores

on Tuesday) on Tim/Kerr Records is the first of these and shows Fahey's

increasing fascination with industrial music and sampling.

The tune that propelled the dozen or so early risers up the aisle was

an example of Fahey's refusal to be pigeonholed. Even when he played

acoustic guitar, he played it through an amplifier and traded the dry,

close-miked sound of his early records for a flat, electronic twang. He

also played several tunes on what might be best termed a prepared lap-steel

guitar, an old aluminum Rickenbacker "frying pan" that had the strings

slacked off to promote Koto-like buzzing and resonances.

The result abetted by slide bassist Jeff Allman was both dissonant

and transfixing and a little like the futuristic electronic squawks and

beeps of the score for "Forbidden Planet."

But the acoustic guitar tunes showed Fahey at his idiosyncratic best.

The notes spun out of his guitar as he music surged and eddied, unbounded

by style here were waves of .tidal fingerpicking backing up to swatches

of Delta blues. He moved a complex fistful of chords up and down

the neck and tickled out weird little nursery rhymes and Transylvanian

dance melodies. He began one song with a gently mutated "Silent Night"

and ended it with a crystalline "0 Holy Night."

In one song, he played a beautiful fingerpicked melody briefly and re-turned

to it later, playing it over and over, setting up a palpable tension and

withholding resolution from the audience. As he repeated that phrase, he

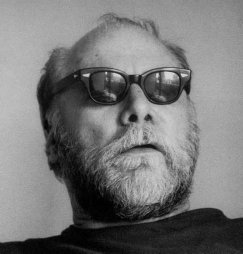

looked off to the side, inscrutable indeed behind white beard and shades,

head nodding to an 'internal beat only he could hear.

And isn't that the way of all true artists?